In early 2019, Google Ads announced that it will be sunsetting the average position metric later this year. At the same time, they launched four new metrics that advertisers could use in its place.

Now, we know that average position will stop being supported in late September 2019. (The most recent target date we have from Google is September 30, 2019.) That date is getting closer—which means you need to make sure you’re ready for the official sunsetting of average position. Here, we’re going to tell you everything you need to know to prepare, including:

- Why average position is going way

- How you can use the new metrics

- What WordStream thinks about this change

Why is average position going away?

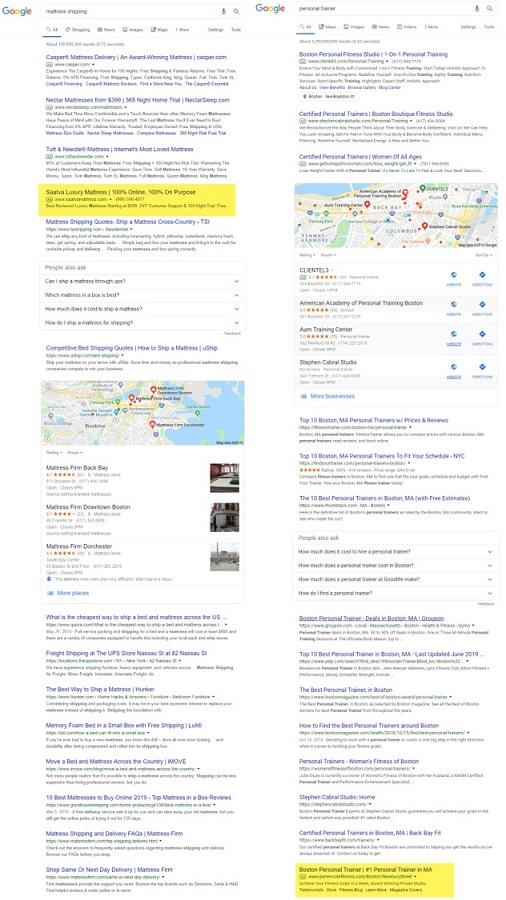

Think about the variety of unique search engine results pages (SERPs) there are for ads these days. Sometimes there are three ads at the top. Sometimes four. Sometimes there is only one ad at the top and the rest are all the way down at the bottom.

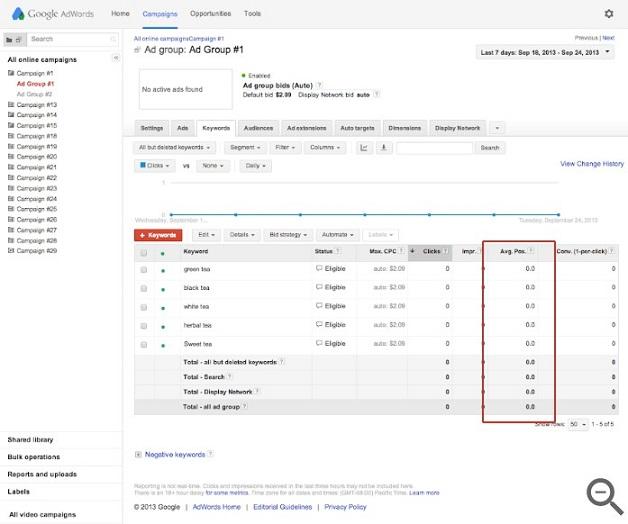

Since Google moved away from the “one SERP fits all” strategy in early 2016, average position stopped being an indicator of where on the page your ad is displayed. Consider the screenshots below. Both of these ads are considered to be in position four on the SERP:

One of these ads will likely have better performance than the other.

Instead of telling you where on the page your ad appeared, average position has evolved into a proxy for ad rank. For example, if your average position is 3.1, you can infer that most of the time, two other ads had beaten you in the auction. But you still haveno idea how often your ad is showing above the organic results.

This presents a problem because ads that appear above the organic results tend to perform better than those that don’t. Without the ability to tell how often your ad appears on top, it becomes much more difficult to answer questions like Will increasing bids improve my click through rate? Or Can I decrease my bids without losing out on performance?

In order to answer these questions (and others), Google created four new metrics.

What are the new metrics?

These new metrics make reference to two relatively new terms within the search space—“top” and “absolute top”—both of which refer to positions on the SERP. “Top” refers to any ad that appears above the organic results. “Absolute top” refers to the very first ad that appears above the organic results. (See the diagram below for more details.)

With those new terms in mind, here are the new metrics:

- Top impression rate [Impr. (Top) %]: The percent of your ad impressions that were delivered anywhere above the organic search results.

- Absolute top impression rate [Impr. (Abs. Top) %]: The percent of your ad impressions that were delivered as the very first ad above the organic search results.

- Search top impression share [Search top IS]: A percentage indicating how frequently your ad appeared above the organic results compared to the estimated number of impressions you were eligible to receive in that location.

- Search absolute top impression share [Search abs. top IS]: A percentage indicating how frequently your ad appeared as the first ad above the organic search results compared to the estimated number of impressions you were eligible to receive in the absolute top location.

What’s our take?

These new metrics provide valuable insight for advertisers—but only if they know how to use them.

Top impression rate and absolute top impression rate are important diagnostic tools. They help advertisers better decipher where on the SERP ads are showing.

Meanwhile, search top impression share and absolute top impression share are more opportunistic indicators. They tell advertisers how often their ads could be served in more prominent positions. While this information is nice to have, it is not as impactful for the majority of SMB advertisers who have limited budgets.

Bottom line: We still think advertisers should focus on metrics that will help them achieve their true business objectives.

Remember, change is the only constant

Google’s announcement that average position was going away was certainly a shock to the PPC community—but it wasn’t that big of a shock